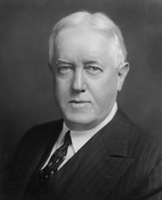

Most researchers using Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr.’s papers want to view his Supreme Court case files. But the single most requested document is not in a case file, or even in his Supreme Court papers. It is the memorandum he wrote on August 23, 1971, shortly before joining the court, entitled “Attack On American Free Enterprise System”. It is widely known as “The Powell Memorandum” or even more simply, “The Memo.” This Tuesday marks 45 years since Powell mailed this the the president of the American Chamber of Commerce.

Though Powell was a moderate Republican in his time, and many of his views might preclude his membership in that party today, it is often cited as a founding document of The New Right.

This was the first document requested from the archives when it opened in the early 1990s and has remained the most popular single topic of research. It would be requested even more, were it not now so ubiquitously available on the Internet. The only place you can find the memo along with contextual primary resources about its origin, however, is in our Scholarly Commons.

On the 40th anniversary of this document, W&L Law faculty member Lyman Johnson wrote a thoughtful piece that was published in the Richmond Times. It is reproduced below:

—————————————————————————

Justice Powell and Free Enterprise

Lyman Johnson

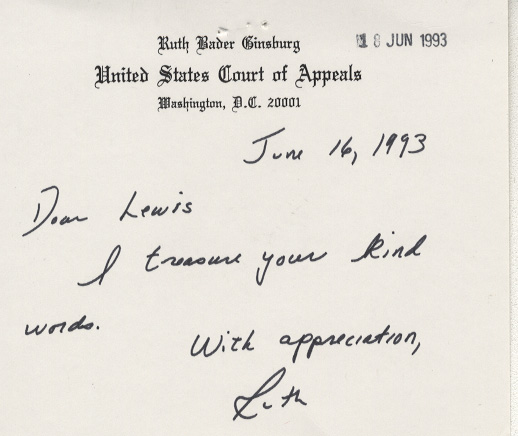

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the “Powell Memorandum,” written by Lewis F. Powell, Jr. just two months before he was appointed to the United States Supreme Court. Captioned “Attack on American Free Enterprise System,” as a playbook for combating leftist critiques of capitalism it was addressed to Eugene Sydnor, Chairman of the Education Committee of the U. S. Chamber of Commerce. Designated “confidential,” the memo’s existence is not widely known, although it has achieved a near-iconic cachet in many conservative circles. Here at Washington and Lee, where Justice Powell attended college and law school and his professional papers are housed, it is the most frequently requested document from a collection that includes a rich trove of remarkable legal memoirs. It is a work that is at once easy to understand and easy to misunderstand.

The memorandum is easy to understand because it clearly and forcefully advances a simple thesis: the American free enterprise system is under attack. Powell, of course, wrote in the midst of the Vietnam War and at a time when a Communist Soviet Union loomed large on the world stage. But he took heartfelt aim at another enervating force − what he called the “most disquieting voices” − those internal criticisms of capitalism coming from “perfectly respectable elements of society.” Of paramount concern to Powell was the college campus, and he spent a good portion of the memorandum decrying the imbalance of ideological views in the university and recommending a host of strong actions in response. He placed particular emphasis on working to attain more ideological diversity (a point he memorably returned to in his Bakke affirmative action opinion) and hiring high quality conservative faculty members who would generate a more pro-business but decidedly excellent scholarly output. Today, looking around at American colleges, many conservatives wonder if anything has changed in 40 years.

And Powell did not spare other eminent groups either, as he pointed a lawyerly finger at what he called articulate and prolific, but ignorant, voices in the pulpit, the media, leading intellectual and literary journals, and among politicians. Of especial concern to Powell in the political realm was what he considered the disturbing demagogic and economically illiterate tenor of discourse that pitted “rich” against “poor” and “business” against the “people.” He called for a more balanced appreciation of the undoubted benefits brought to the American people by our business sector. This regrettable polarization in our discourse about the place of business in a democratic society continues today, and business elements likely cheer Powell’s stirring defense of free enterprise, perhaps because so many today seem unable to mount their own compelling case for a system they spend their lives in. Of course the memorandum is beloved in such circles.

But the memorandum, and the views of the man who wrote it, are easy to misunderstand as well. Powell was no knee-jerk apologist for an unbridled, money-centered vision of big business. Powell was both a nuanced thinker and a conservative. We are trying still in this country to sort out what it means to be both. Powell, a Virginia patrician to be sure, wished to preserve – and improve – those institutions he considered vital to democratic society. On the public school front, for example, he chaired the Richmond School Board during the stormy desegregation era of that city and he worked to end the practice of massive resistance in Virginia. He was President of the Family Service Society, an agency providing aid to those in need. Civically-engaged and active in the community and bar long before he became President of the American Bar Association, he fervently believed in those private sector venues that, as Robert Nesbet once put it, serve as critical “buffering and mediating forces” between the individual and state.

His conservatism extended into the corporate realm as well. But it is a strain somewhat forgotten in the business mainstream today, although it has a long lineage. In the memorandum itself – written a year after Milton Friedman’s famous if simplistic NY Times defense of profit maximization as fully discharging a company’s social responsibility – Powell refers to an executive’s obligation of “maintaining a satisfactory growth of profits, with due regard to the corporation’s public and social responsibilities.” And in an important 1982 concurring opinion that laid the groundwork for state efforts to successfully craft anti-takeover legislation eventually upheld by the Supreme Court in 1987 – in an opinion Powell himself wrote – he spoke of the “public interest.” He was concerned about takeovers of small and regional target companies, and about the disruptive effects on local economies caused by abruptly moving headquarters after corporate acquisitions. The social fabric of a place and the principle of a sometimes market-clogging federalism mattered to Powell. Unfettered markets were not the highest good to him, or to many other conservatives of a non-libertarian stripe who saw (and see) the roles business and government each can play in advancing the common good. For Powell, a consummate corporate lawyer, a corporation, whatever it may be at law, was, socially, far more than its stockholders and managers.

Powell could see both sides of an issue, a judicial quality for which he became famous and criticized. As business leaders and other defenders of free enterprise today remember and rightly laud his spirited defense of capitalism, they should also take to heart his call to attend to their own responsibilities to preserve and enhance the corporate institution’s role in society. What exactly that means in 2011 is a subject on which we could use a thoughtful and balanced discussion. And we should attend to it with Powell’s exquisite civility.

In a short time, however, he was ensconced in the house (see below) in the Forest Hill district of Richmond that would be his home until leaving for college.

In a short time, however, he was ensconced in the house (see below) in the Forest Hill district of Richmond that would be his home until leaving for college. At any event, he appeared to have been a happy baby.

At any event, he appeared to have been a happy baby.